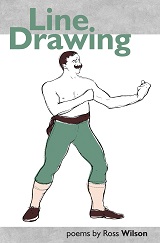

Line Drawing

Ross Wilson

Price: £7.99

Ross Wilson’s long-awaited first full collection Line Drawing explores the fault lines between people and the lines that connect us. Drawing on his experiences as a low paid worker and as a schoolboy boxing champion, Wilson takes a line for a walk between production lines, life lines, sword-lines and the wafer-thin line between civilisation and barbarism. Line Drawing is a tough-minded, tender-hearted book, moving from violence towards the possibilities of love and compassion.

Who knows what started it? Probably not the man who hit his brother, or the brother who hit the floor. Probably not the girl, her rouged lips a wound spurting, ih’s yir brithir! ih’s yir brithir! I lost interest, wondering if this spot by Dunfermline Abbey, this club, Life, was where Henryson wrote his fables, and if thinking is what separates us from animals. Who knows what Cain was thinking, cuffed in a van. Or Abel, buried with the cause of all the trouble under a rubble of chairs and glass. Or the war-painted banshee wailing like the Black Douglas when he charged into blackness seven hundred years ago, the heart of the Bruce in his fist like a bomb to throw in some Holy War in the name of God or some such thing our thinking inspires us to fight over.

Lines were scored in the dirt in early boxing matches when a knockdown, not a bell, concluded a round; if a pugilist couldn’t ‘toe the line’ or come ‘up to scratch,’ he was ruled Out of Time. To deter members of opposing parties from attacking one another in the House of Commons two red lines were marked, two swordlengths apart, on the floor. MPs were and are expected to stand behind these lines when a speech is in progress. Emerging from Southwark Station, looking for Tate Modern, I imagined this area back when bear-baiting and cock-fighting were common, and actors strutted their hour at the Globe. Stumbling on the Ring Boxing Club, I thought, how appropriate a space to exhibit the noble art should be so near the Tate. Then, a second thought that was more of a picture: Two-Ton Tony Galento, a boxer from the thirties who trained on beer and refused to shower weeks before a fight; who, according to Max Baer, stank ‘like rotten tuna and old liquor sweated out;’ who, when asked what he thought of Shakespeare, said, ‘I’ll moider da bum!’ A hairy bear of a man, Two-Ton Tone applied gouging, biting, butting, low blows and kidney punching to what some call the sweet science, others, the noble art. In black and white footage of him he brightens the screen like a cartoon. The owner of a New Jersey saloon. I saw him clearly in London four hundred years ago, betting on a chained bear versus dogs, and toeing the line men have always drawn in the grime.

To write about boxing is to be forced to contemplate not only boxing, but the perimeters of civilization – what it is, or should be, to be ‘human.’ Joyce Carol Oates, On Boxing I remember watching Frazier v Bugner. Bugner was out on his feet, Frazier about to him him again before the referee could intervene. Set to deliver a final punch, this champion of violence stopped, stepped back and let his victim sag to the canvas in a delayed reaction. What sportsmanship! What sportsmanship! The commentator announced. Those words and images returned to me as I watched a man go down hard in a cage while another ran at the prone body to hit it again and again until, finally, the referee pulled him back like the auld saying: You don’t hit a man when he’s down used to restrain us, or most of us, like a proverb few remember as other ideas pollute the air, whispering into the ear: Survival of the fittest. Strong eat the weak. No such thing as society.

How could a man hit a man with a hammer? We know the reason – drug-money. But how could he grab and raise and swing such a thing as a hammer, and bring it down upon the head of another? I once hit a man so hard his nose burst over his trainers. Later, he laughed at it still bleeding after a shower; we’d been sparring, practising for the real thing with big sixteen oz gloves. A skinny teenager did that with one left hook – my weak arm. The hand I write with is stronger. It asks: how could a man hit a man with a hammer? And holds the answer in itself.

Boab attended a Cambridge lecture on the moral philosopher and economist, Adam Smith. Tired after a shift selling stuff, the tsk of his lager can didn’t bring one tut to a student lip: the lecture, a recording on Youtube, was at least five years old and thousands of miles away from his home town, Kirkcaldy. Kirk caddy, the lecturer called it, but what did he ken? What ye watchin’ that fir? Boab’s wife demanded to know, that’s no fir the likes ih us. He had to pause and scroll back to what her voice made him miss; someone had asked a question: did Adam Smith define wealth as money? No, well-being. A few days ago, Boab ate a pie by the High Street bakers, observing a plaque consumers ignore, explaining how Adam Smith lived here, and how this was where he wrote The Wealth of Nations. Boab had thought a visitor could be forgiven for thinking Kirkcaldy was called Toilet. TO LET signs jutted over shut shops all around him. Under one, the bollard of a beggar was avoided by a man on his way to the Jobcentre, a Jobseeker’s Allowance booklet stuffed into his back pocket like an empty wallet; the image of it clear as old photos Boab had seen of the town’s linoleum and linen factories, now shut down, or in ruin. Boab scratched his belly, feeling something had to be in gestation. For things had to change soon, he thought, reaching for another cold can.

Across the border they’d be chavs. Here, they’re neds, and almost proud, as if to be a ned was to have a trade; their tracksuits overalls, Buckfast bottles tools. They drink by a stone in a park near a railway station in the dark unable to see what the stone’s supposed to be. A lighter reveals words about a civil war in Spain. Across the rails a memorial garden is maintained for lives laid down in the Great War for Civilisation and all the wars that came after civilisation was won. Wiy’s this stane here, no there? What made this war diffrint? Ma pal’s pal wis killt in Afghanistan – what stane will his name be oan? Just then, headlights of a police van across the road, hit them like an interrogation light, bright with questions of its own. A voice called like a cue to act out the role they’d been given or the life they’d chosen, depending on what side of the line we choose to see them from. Near a public library and museum, art gallery and memorial garden, across the tracks, on the steps of the Adam Smith Theatre, a man and woman exit Macbeth as three boy-men run by a train and enter a scene they’ve no part in.

‘A unique voice, and a very important one, on the contemporary Scottish poetry scene.’

Magi Gibson

‘Humour, tenderness and a political conscience that neither preaches nor hides behind a bushel. On top of raw power, there is also technique. Surprising imagery is commonplace in Wilson’s poetry.’

Christie Williamson

‘Emotionally honest and with his own take on a masculine vulnerability, Ross Wilson’s collection has much to say and says it from the heart.’

The North

‘Wilson’s world rarely appears in the softer, more comfortable bookish scenarios inhabited by much contemporary poetry, but this pamphlet gives the reader an insight into equally valid experiences.’

Happenstance

‘a hard-hitting collection.’

Scotsman