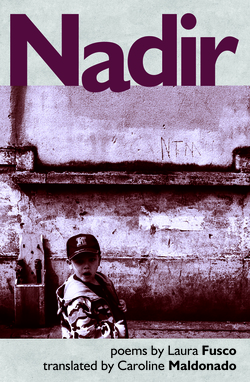

Nadir

Laura Fusco

Price: £8.99

There are 35 million child refugees in the world today; over a million were born in flight, in exile, in camps. While a great deal has been written about the suffering of those who are fleeing persecution, displacement, hunger and war, in Nadir Laura Fusco attempts to record the voices of the refugees themselves, especially the women and the children.

Nadir is a book about desert caravans, dangerous sea-crossings and desperate marches, about fences, camps, detention centres, squats and underpasses. It is a portrait of ‘a crowd of a hundred solitudes’, the wretched of the earth, the defeated who refuse to accept defeat.

Cover photo: Nathanael Fournier, Avenue de Dunkerque, Lilli 2008

Author photo: Monica Noa Buraggi

As if it were nothing when there are thousands. It isn’t political it’s maths. They aren’t immigrants They aren’t refugees They aren’t clandestine They are children someone says. And: children are all the same It’s not true they are all the same It’s not true they aren’t clandestine. And sometimes not even that they are still children.

To be 1 year old. To be 1 at 1. With whatever one should have and do at 1. To be 5 years old. To be 5 at 5. With whatever one should have and do at 5. And 6 at 6. It should be inconceivable that one can and must draw up a list of what they ought to have. And what they should not endure. To know that what they imagine will be theirs. (But it’s already like that even if it doesn’t seem so).

An ochre and gold snake, red pink fuchsia, orange, yellow, green, light blue, indigo, violet. As fast as clouds, highly-coloured contrails. No wall will do it. When they have to keep still in a square metre of fever or on the cot they get bored close their eyes and imagine. When they have stomach-ache, nightmares, are frightened or angry they turn away from each other, close their eyes and imagine. In between what they imagine and reality there’s a space they know and run towards without stopping, even when they’re doing nothing, even when they don’t know it and cry or play or are just afraid. After so many steps now that I’m only one step away from No wall will do it. Even if their struggle is imagined. Gold ochre pink red fuchsia orange is more real than any power more than any person who writes They have suicidal instincts, continual nightmares. Sometimes they consider violence normal. They learn it to enact it. They’ll become insensitive to pain, They’ll abuse drugs and medicines, they will abuse. Someone dies or gets lost in their imagining like the passeurs on their mountain crossings, because to imagine is their crossing and that’s the reason the world is theirs. Where the only storm is the doubt that dreaming might not have power over what they see and feel and touch but they leave to grown-ups the illusion that a camp is more real than the story they are writing, eating, sleeping, waiting for, thinking. Spaces and times that aren’t there yet open up for them to pass and exist for them to pass and open towards another way of existing. Gold ochre red pink fuchsia orange...

He’s sitting on the orange lotus flower on the bedspread. His mother is 16 but he can’t count. For him she’s his mother but this morning she’s under a gold cover and her eyes are closed. Her sister’s crying. He doesn’t want to cry. He doesn’t want to look at her. Better to play.

Images are their ghosts they will stay with them always forever. Even if they go to the camp’s psychologist they’ll still take medication. Waves of obsidian. Sky the colour of turmeric. Clouds blown up until they explode. At home it was a journey to go and fetch the water but this time it was the water that came onto the deck of the boat and carried her away. A thud. A wave collapses where the bodies are. There was mother’s. She should have kissed the earth because she was alive like sailors who survive storms. Instead, she doesn’t speak, doesn’t eat doesn’t sleep. To heal is the only journey. The rest is kilometres and days to get through, kilometres.

The sky’s asleep. The night’s light so heavy that a spiral of smoke instead of flying curves towards land and descends. Fog – or is it smoke? – still clings to the trees. And creates new forms and new shadows. We can’t live without free wi-fi. We want sky sport, a charger for our mobiles, they have a Britney Spears ringtone. She comes out dressed in a chador on which she has pinned flowers made of rags. Nearby they throw out sofas, chairs, set fire to bedding to film a video and post it, to protest, out of boredom, they queue up to pee and for ‘wages’, The men quarrel, yell, kill themselves, die. While the women, writes the reporter ‘try to make up for the atrocity the children have witnessed with their gentleness.’ They try to get them to sleep, to wash them, not make them cry. To be normal and to do normal things that is both women’s fortune and their revolution. And from normal things comes the future. Even here.

‘Laura Fusco's poetry is spoken with pebbles in her mouth, salt, broken glass. It tells the world what the world does not say. Laura Fusco's poetry is political, when the word political no longer means anything in the mouths of the politicians. It tells us about women, men and children who might be ourselves, but whom we don't want to recognise. Laura Fusco's poetry reminds us of our human duties.’

Philippe Claudel

‘This is poetry as testimony, away from self-indulgence ad excessive subjectivity and towards forms which can properly engage with the mass tragedies which characterise our times.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed

‘Laura Fusco’s poems are the best I’ve read on this subject,’

Adele Ward

‘It is the extraordinary mass and variety of exactly truthful particulars that gives this sequence of poems its persuasive force. Even now, in the midst of a world-wide sickness, the movement of desperate people across frontiers continues. Fusco helps to keep those people on our consciences.’

David Constantine

‘tremendous… unsentimental and immediate.’

The Italian Rivetter

‘brings refugees’ lives to the forefront, thrusting their hopes and fears, their plight, their common humanity before the reader.’

Modern Poetry in Translation