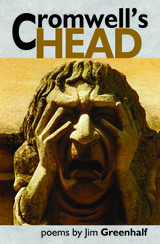

Cromwell’s Head

Jim Greenhalf

Price: £7.99

In 1661 Charles II ordered Oliver Cromwell’s corpse to be exhumed and decapitated. The head was displayed for over twenty years on the roof of Westminster Hall as a warning to republicans everywhere. Cromwell’s Head looks at history through the eyes of Britain’s first and only republican leader, telling the story of a ‘headless people’ who were forced to march to the top of the hill and down again – from the violent end of empire to the coronation of Charles III. Grimly comic and comically grim, a natural sequel to Jim Greenhalf’s previous Smokestack collections Breakfast at Wetherspoons and Dummy!

Author portrait by Pete Cushway

I Did you see it, the last boat leaving? Thank God they’ve gone. Good riddance. All those years they’ve been telling us what to do and how they want it done. Things can only get better now, they say. No more Pax this and Pax that. When was the last time we did anything out of order? That’s what they’ve done to us. The light will be purer now that its gleam is unsullied by blood and eagles in their arenas. And they call us barbarians! They treated us like refugees in our own country: changing our habits, our customs, words; taking our women, thrusting themselves at us like belly-piercing swords. We paid for their empire, did their dirty work, served as auxiliaries, while they tossed off in their hillside summer villas. Why did we let them do it for so long? II Well that’s that, then. Four centuries of empire in our wake. Down the hole. I’m sorry to be going back. Nothing glorious in that old ruin of slaves and foreigners, pouring like water across our borders. Were we too dependent on them to keep our way of life in order? They said they were serving us, but weren’t they also serving themselves? They knew we hadn’t the money to pay for our armies at home and abroad. Fiddling, corruption, laziness, cowardice: did we civilise the world for this? We, who stand on the shoulders of indomitable men of steel and marble? I’ll piss in the cup and pour a libation on the head of any fat pontificating fool, beating out the rhythm of our decline like some mad hortator, dragging us back to that bargain basement of fools and whores. They won’t survive; without us to protect them they’ll be eaten alive by jackals and wolves. Too late for warnings. Do you think we’ll be missed?

As the last US Sea King rises above Saigon, again; as bulletins ricochet and the old newsreels are re-run – jet planes crashing in, topless towers imploding; brown shirts, black shirts, on the march – are the last days of Pompeii really here again? Aristotle told world-conquering Alexander: beware of history repeating itself. First as tragedy then as farce, Karl Marx or Brian Rix added two thousand years later. Having survived the news of wars, wars, wars – Ulster, Iraq and Afghanistan – am I, are we, any wiser? We are mostly in the dark, drip-fed by plasma screens the size of football pitches as, once again, farce bleeds into tragedy.

Does all the murdering maiming us daily signify a world that’s gone to the devil? After all, Goodwood continues, the towers of Ripon Cathedral still stand, lifeboats and air-sea rescue risk life to save it. With or without God, death does not go unopposed. We say, better the devil you know; but what if death, famine, pestilence and war are the only things you know? Better a fool than a monster with a vision. Prospero’s brave new world of cloud-capped towers and gorgeous palaces is best left to Disney – not a brownfield site on the road to Damascus.

Roads are being cordoned off with cones. Around local war memorials men in high-vis bibs arrange municipal chairs, in readiness for the traditional fibs. On the grid of a car-park where council offices used to be, portable cabins raised on blocks are staffed by masked recruits in blue. They offer life-enhancing shots to my lucky generation which escaped conscription when the law was changed and we were freed from the compulsion of compliance. I see the young gathering again, arranged by uniform in ranks. The discipline of doing this gives them shape and purpose, I suppose. I lasted a day in the Boys’ Brigade. The Queen cannot manage the Cenotaph this year. Next year, or sooner, the wreath may be hers, as the nation, collectively, bids goodbye or good riddance, to the second Elizabethan era. Big guns will salute her passing into history, as they announced her entry in 1953. When she’s gone, I fear, we’ll all be charlies. November 2021

Tuesday, monarchy ends on the block. The day after, business as usual – the real shock. Everything going on as it did before two that cold afternoon when they stopped the clock. the King’s head was sewn back on, the thread tied in a Windsor knot. Nature appoints the wise to govern the foolish, Milton wrote. But what’s the news when nature loses its head, and fools are empowered to rule instead?

It took eight blows of the Tyburn axe to separate Oliver Cromwell’s head from the body that carried it through Civil War and England’s first and only Republic. Impaled on a twenty-foot pike outside Westminster Hall for all the years of the cocker-spaniel Parliament, as though a monstrous shrike had fed on the Lord Protector: plucking his eyes, then picking his brain, as successive heads of state rolled into Westminster and out again. Bought and sold, passed around, for three hundred years Cromwell’s eyeless head stared impassively as the battles he fought and won had to be fought all over again. Until the ground we stand upon was ceded, surrendered or given away by fools, self-seekers and worse whom he had driven out of Parliament. A Bible and sword his ball and sceptre. In the reign of Elizabeth Windsor, Cromwell’s head went underground; but still it watches all that’s done in the headless people’s name. At a time unordered by rhyme or reason. Call Andrew Marvell from his garden to compose another ode for Cromwell’s pardon.

‘respects the reader’s intelligence, feeling its way into the minds of its narrators, not preaching at us…’

Sheenagh Pugh

‘I really like the way the biographical, the autobiographical and social commentary are balanced.’

Michael Stewart

‘There is a rigour and honesty to his writing which mocks sentimentality, and a blackness to his humour which is so well controlled that it never collapses into cynicism.’

Yorkshire Post

‘Greenhalf paints himself as moody, grumpy, awkward, a peripheral nay-sayer... but in these poems he is good company.’

Mistress Quickly’s Bed

‘bold and poetically rich… accessible yet challenging.’

London Grip